Oppenheimer used Sanskrit verses − but not the way Christopher Nolan’s film depicts it

A scene in the film “Oppenheimer,” in which the physicist is quoting a Bhagavad Gita verse while making love, has upset some Hindus. The information commissioner of the Indian government, Uday Mahurkar, said in an open letter the scene was a “direct assault on religious beliefs of a billion tolerant Hindus” and alleged that it amounted to “waging a war on the Hindu community.” He also said that it almost appeared to be “part of a larger conspiracy by anti-Hindu forces.”

It is hard to say how many Hindus were offended by the Gita quote in a sexually charged scene, but there were those who disagreed with the views expressed in the tweet. Pavan K. Varma, a former diplomat, wrote that the controversy was a “misplaced outrage.”

Some others were not offended, just disappointed that the context of the lines quoted from the Bhagavad Gita was not brought out well. I should also add that Hindu texts composed over 1,000 years, starting around the sixth century B.C.E., have Sanskrit mantras for every occasion, including reciting some ritually before having sex. But they are context-specific, and certainly the Bhagavad Gita would not be used.

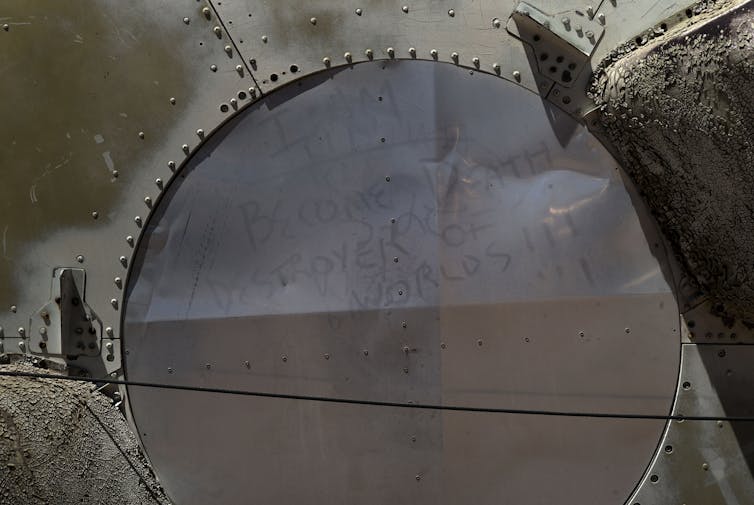

Overall, the controversy brought attention to the words quoted by J. Robert Oppenheimer while looking at the erupting fireball from the atomic bomb explosion in Los Alamos, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945: “Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” These words are a a paraphrase of Bhagavad Gita 11:32 where Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu – whom many Hindus think of as the supreme being – says that he is kala, or time.

Kala also means “death.” Oppenheimer’s teacher, Arthur Ryder, a professor of Sanskrit at the University of California, Berkeley, had translated the verse as “Death am I, and my present task Destruction.”

Beyond the sex squabble, the biopic can be a good starting point to understand how Oppenheimer’s deep knowledge of the Bhagavad Gita and other Sanskrit texts helped him with his assignment in New Mexico. It can also be a catalyst for the public to have some hard conversations about weapons of mass destruction.

Wisdom of the Gita and the Panchatantra

As an undergraduate at Harvard University, Oppenheimer read Hindu texts in translation, but at Berkeley, he learned Sanskrit from Ryder, meeting in his teacher’s home on long winter evenings. On Oct. 7, 1933, he wrote to his brother Frank that he had been reading the Gita with two other Sanskritists.

This text was special to Oppenheimer, more than other books. He called it “the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue,” and he gave copies to friends. When talking at a memorial service for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, he quoted his own translation of Bhagavad Gita 17:3, “Man is a creature whose substance is faith. What his faith is, he is.”

Oppenheimer’s reaction, when he looked at the mighty explosion, seems to be close to what the German theologian Rudolf Otto called “numinous” – a combination of awe and fascination at this majesty. His reaction was to think of the Bhagavad Gita’s verse 11:12: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.”

Oppenheimer also read many other Sanskrit texts, including the fifth-century Sanskrit poet Kalidasa’s “Cloud Messenger,” or “Meghaduta,” and his letters show familiarity with “The Three Hundred Poems of Moral Values,” or the “Satakatrayam,” a work from the sixth century C.E. From his quoting the text in many contexts, he seems to have been fond of the Panchatantra,“ a text of animal fables with pragmatic morals. Ryder, Oppenheimer’s Sanskrit mentor, had also translated this book of charming stories with sometimes cynical messages.

Oppenheimer’s familiarity with the Panchatantra is also evident in the naming of his new car Garuda, after the eagle-vehicle of Lord Vishnu. He explained the name to his brother, not with the bird’s well-known connection with Vishnu, but by alluding to a lesser-known story from the Panchatantra, in which a carpenter makes a wooden flying vehicle shaped like the mythical Garuda for his friend.

Oppenheimer loved a Sanskrit epigram from the Panchatantra: “Scholarship is less than sense, therefore seek intelligence.” The line is a rueful reflection at the end of a story in which four men go to seek their fortune.

Three of them were learned scholars who held the fourth in low esteem. On their path, they came across some bones. On seeing those, the first, believing the bones to be of a lion, said that he could put the skeleton together. The second said he would the graft skin and flesh on it, and the third said he would make it come to life. The fourth – believed to be the less learned person – warned them against it. However, when they insisted on going ahead, he asked them to wait until he could climb a tree for safety. The lion came to life and devoured the three scholars.

Oppenheimer used the Sanskrit verse that followed this story often. From the Gita, he learned and rationalized that it was his duty to build the bomb, and it was the leaders’ duty to use it wisely. In other words, Oppenheimer went along with government decisions not because they were government decisions but because he thought political decision-making was the duty of government leaders, not scientists.

A missing discussion

It is hard to know director Christopher Nolan’s motivation for juxtaposing the Gita verse with an intimate scene – it could be creative license or simply Orientalism, or the West’s stereotypical description of the East. Given Oppenheimer’s deep love for the Bhagavad Gita, he would not have, I believe, quoted the text with disrespect.

As for the Hindus who are offended, there could be multiple reasons: It could be the centuries of a colonial gaze that was fascinated with and horrified by the erotic in Indian spirituality.

For example, the 10th-century temples of Khajuraho – where only about 10% of the sculptures are erotic – and texts like the Kamasutra informed early missionary views on Hinduism. It could also be that some Hindus valorize the spirit of renunciation and the ascetic impulse of some Hindu texts.

But beyond this controversy, this film offers an opportunity to reflect on more profound issues. The detonation of atomic bombs led to the death of possibly 200,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and horrific effects on survivors. Kai Bird, coauthor of the book on which the biopic Oppenheimer is based, said that he hopes the film “will initiate a national conversation not only about our existential relationship to weapons of mass destruction but also the need in our society for scientists as public intellectuals.”

While that would be valuable, an important discussion, left out from the narrative, is about the ethics of American leaders who knowingly caused harm at the time. The atomic test explosion led to devastating health consequences for about 13,000 New Mexicans who lived within a 50-mile radius and were not warned beforehand or afterward. This exposure to radioactive material took a toll over several generations.

In the end, the lesson is that the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita have to be balanced with the pragmatic lessons of the Panchatantra. Despite Oppenheimer’s quoting the Panchatantra about common sense being more important than intellectual scholarship, his own interpretation of duty gave undue credit and power to political leaders.

With the atomic explosion in New Mexico, the lion from the Panchatantra story that Oppenheimer cautioned about did come to life, and some may say it lives in a straw cage.![]()

Vasudha Narayanan, Distinguished Professor of Religion, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.