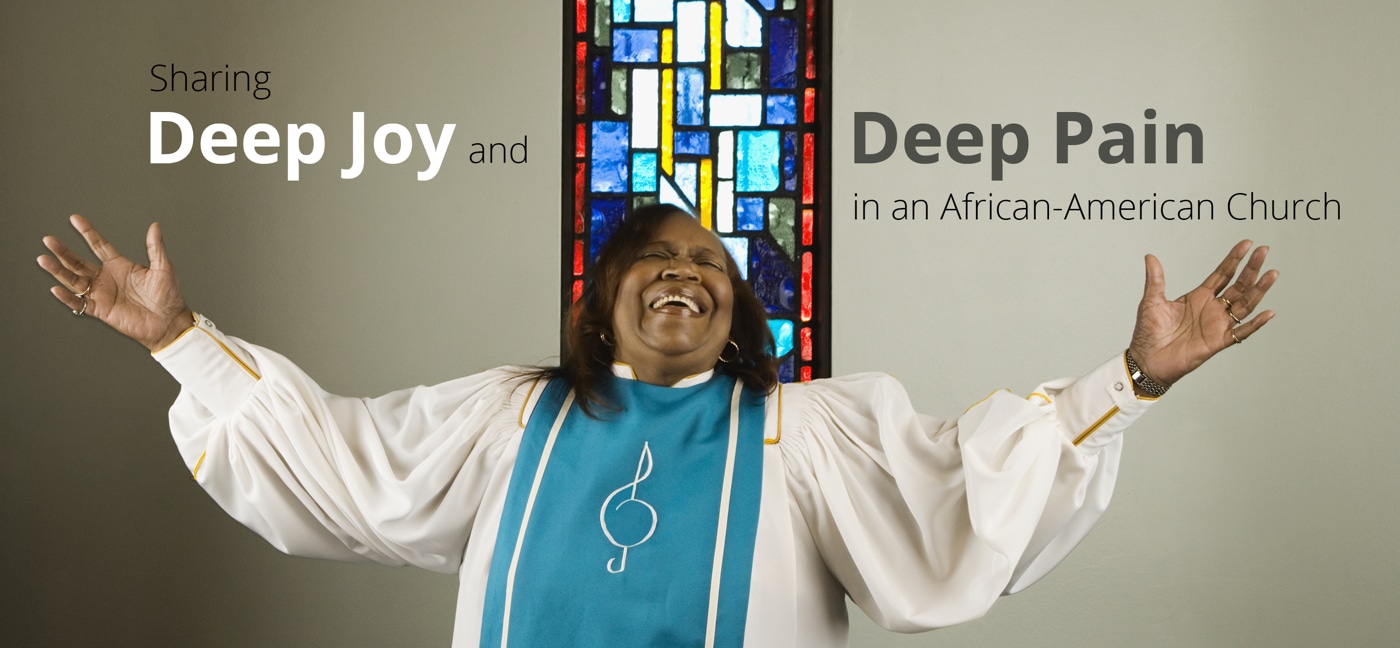

Sharing Deep Joy and Deep Pain in an African-American Church

I wasn’t sure what I was expecting when I walked in the door of Christ the King United Church of Christ (UCC) in the fall of 2014. I just knew that I had to be in church, but I didn’t know where to go. My family and I had moved to St. Louis a year earlier, and it still felt like an unfamiliar place. When African-American teenager Mike Brown died on a street in Ferguson the previous month, just a few miles away from our house, I knew I needed a church community to help me mourn, to take this moment of fracture—both mine and that of the larger community—and nourish it into something new.

On the face of it, Christ the King was a lot like the church I had been a member of for 25 years in North Carolina. It was part of the same denomination, a liberal Protestant tradition that prided itself on advocating for progressive social causes, including women’s ordination. The minister at Christ the King, the Rev. Traci Blackmon, embodied what the UCC calls its “radical inclusiveness.” But my church back home, for all of its expansive outreach, consisted of a large, fairly traditional, white, affluent congregation in a college town. Christ the King, on the other hand, perched right next door to Ferguson, was small and strapped for money. And the congregation, at least the gathering I could see on Sunday mornings, was all African-American.

I’d like to say that this was an entirely comfortable transition. I’m a scholar of religious history and have taught and written about African-American Protestantism for over three decades. I have attended plenty of services in the black church tradition as a guest and observer. I knew about altar calls, shouting, and prayers that lasted twenty minutes. I even knew the words to some of the gospel songs.

It was harder to know what my whiteness might mean amid such raw racial fracture. But I was raw too, in my own way: I entered there in need of something I couldn’t even identify, an acknowledgment of feeling and experience, that I hadn’t found in the predominantly white UCC churches in town that I’d visited. I came not as an expert ready to interpret this experience, but as someone hurt and angry and in need, both for myself and for this new place I wanted to call home.

What did I find? I found a willingness to talk openly about the gaping wounds in our city that divided us by race. I heard a call for love enmeshed with a vivid and persistent thirst for justice. I saw a community that opened its doors to all-comers, including a homeless man who occasionally showed up and even interrupted the service a few times—and I saw his cries met with attention and acceptance. I met a congregation that didn’t find it weird to see a lone white woman showing up week after week; they just kept right on hugging me.

Most of all, I discovered at Christ the King an astounding mix of joy and pain, both of which were embraced and welcomed in. It is a church that can hold it all because it has to. One sunny Sunday morning we gathered outside the sanctuary after the service with over 100 red and black balloons. As Rev. Blackmon spoke the names of all the victims of gun violence in St. Louis over the past year, we let them sail away into the air. She then asked others to name loved ones who had been shot and killed. At least two dozen people in the gathering identified family and friends lost. So much grief to bear.

Yet it’s the joy and love that nourish people. There’s a lot of great music, and plenty of potlucks after church. And there is a great deal to celebrate: weddings, births, graduations. We take time during the service to praise the young people who are achieving remarkable things and getting good jobs. Sometimes I get antsy when the service goes past the two-hour mark or when the choir launches yet another verse. I’m never convinced I like the keyboard playing in the background during the prayers. None of this is the “white” Protestant tradition in which I was raised, where you felt self-conscious coughing out loud during the service.

Is this holy envy? Close, but not exactly. It’s more of a fellowship of the heart. Christ the King isn’t a typical “black church” any more than there is one typical “white church.” But I do think there is a lot that many white Protestants could learn about loving and living together in community from their brothers and sisters in African-American Protestant traditions. How to hold and share deep pain and profound joy, and most often both at the same time. How to sing and pray as if your life depended on it. How to welcome whoever God brings through the door.

Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp is the Archer Alexander Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Washington University in St. Louis and the author of Setting Down the Sacred Past: African-American Race Histories.

Editor’s note: This essay is part of an ongoing series on Holy Envy. People of various religions explain what they admire in other faiths. The purpose is to increase understanding and solidarity between believers.