Muslim Americans assert solidarity with Black Lives Matter, finding unity within a diverse faith group

The killing of George Floyd took place at the doorstep of Muslim America.

He was killed in front of Cup Foods, a store owned by an Arab American Muslim, whose teenage employee – also a Muslim – had earlier reported to police that Floyd tried to use a counterfeit $20 bill to buy cigarettes.

Muslim American businesses are common in lower-income areas, such as the part of Minneapolis where Floyd died after a police officer knelt on his neck. And as the writer Moustafa Bayoumi has noted, this puts stores in a precarious position – catering for the community while also duty-bound to report crime to the police, sometimes under the threat of being closed down if they don’t comply.

As a Muslim scholar of Islam who has written about the role of Muslims in the making of the United States, I recognize that the circumstances of Floyd’s death hint at the proximity and complex relationship that different sections of America’s Muslim community have with law enforcement and with the Black Lives Matter movement.

‘Too often silent’

Since Floyd’s killing, Muslim Americans have mostly shown solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Mahmoud Abumayyaleh, the owner of Cup Foods, has said that the store will no longer call the police on customers. Nationally, there have been numerous statements from groups such as the Muslim Public Affairs Council, the Council on American Islamic Relations and the American Muslim Institution.

A joint announcement by over 35 national Muslim civil rights and faith groups and more than 60 regional groups noted that Black people were “often marginalized” within the broader Muslim community. It continued: “And when they fall victim to police violence, non-Black Muslims are too often silent, which leads to complicity.”

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

There have been Muslims in America for almost 500 years. Estevanico the Moor was brought as a slave to what is now Florida in 1528 and is memorialized on the Texas African American history monument as the first African to enter Texas. At least 10% of the slaves brought from West Africa were Muslim, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture tells some of their stories as part of its collection.

But, many African Americans came to Islam later through the Nation of Islam, which wove a Black nationalist element into their faith.

Speaking up

Black Muslims played a crucial role in the U.S. civil rights movement. Even today, quotes and images of civil rights activist Malcolm X, who converted to Sunni Islam in 1964 after leaving the Nation of Islam, remain potent in the current protests.

Meanwhile Muhammad Ali, who at one time was perhaps the most recognizable Muslim in the world, gained fame as much for his political stances as his boxing prowess. Ali led the way for other Muslim American athletes who have pushed for social change, including NBA great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who was involved in discussions by the Olympic Project for Human Rights for Black athletes to boycott the 1968 games.

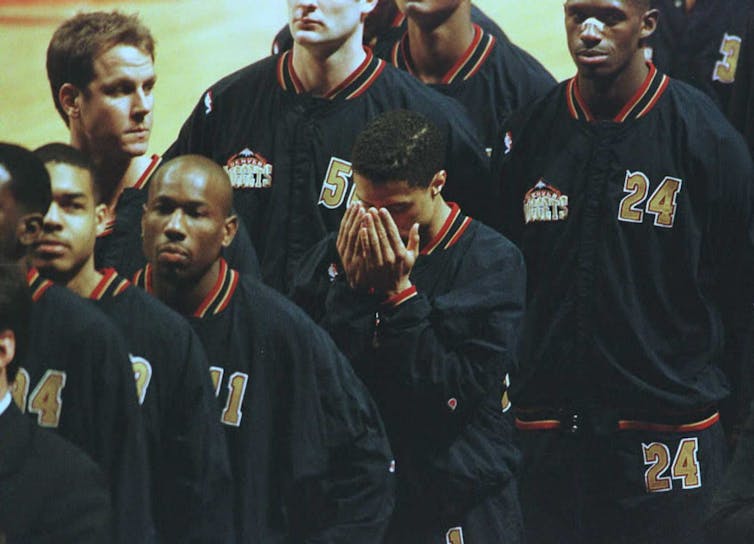

And 20 years before Colin Kaepernick, NBA player Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf refused to stand for the national anthem while playing for the Denver Nuggets because of his “Muslim conscience.” Polling shows many of these protests were greeted with disdain by the majority of white America.

Today, at least 20% of Muslims in the U.S. are Black Americans. But starting from the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, there has been a growth in immigrant Muslims coming to America.

While increasing overall numbers of Muslims in U.S., immigration has created a dividing line in the American Muslim community – between Muslims with an American heritage that stretched back generations and newer arrivals. Immigrant Muslims were often assumed by American Muslims to know more about Islam as they came from Muslim majority countries, and so they were given more authority in Muslim organizations and as Islamic leaders.

They also built mosques that served their own ethnic communities, with immigrant Muslim communities often worshiping separately from Black American Muslims.

There is also a split in the economic status of American Muslims. According to the Pew Forum, 24% of American Muslims have an annual income above US$100,000, while 40% have an income below $30,000. Many of those who are wealthy – like billionaire Shahid Khan, an immigrant from Pakistan who now owns the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars – are from immigrant Muslim communities.

Police and protests

The intersection of race, class and national identity means that views vary on issues such as police, protests and discrimination. A 2019 survey found that 92% of Black Muslims believe there is a lot of discrimination against Black people, compared with 66% of non-Black Muslims.

Nonimmigrant Muslims are more likely to have lived out the history of the United States, including the unjust legacy of slavery. As Americans, they were also taught early on and often that the right to protest is protected under the Constitution.

Immigrant Muslims may have a very different experience with protest if they come from a country where dissent can lead to imprisonment or death. They may also be more wary of being seen as “anti-American.” Immigrant Muslims expressed more pride in being American than U.S.-born Black Muslims, in a 2017 Pew poll.

Both communities, however, share a complicated history of U.S. law enforcement. For Black Americans, police violence dates back to slavery. Since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, police in cities like Los Angeles and New York have tried to infiltrate and surveil American Muslims.

In vowing to stop calling the police on its customers, the Muslim-owned Cup Foods in Minneapolis is standing in solidarity with the largely Black community it serves. In a similar fashion, the soul-searching that has followed Floyd’s killing provides an opportunity for Muslim Americans of all backgrounds to unite and side with the oppressed, many of whom share their faith.

Amir Hussain, Professor of Theological Studies, Loyola Marymount University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.