Sen. Ossoff was sworn in on pioneering Atlanta rabbi’s Bible – a nod to historic role of American Jews in civil rights struggle

Jonathan D. Sarna, Brandeis University

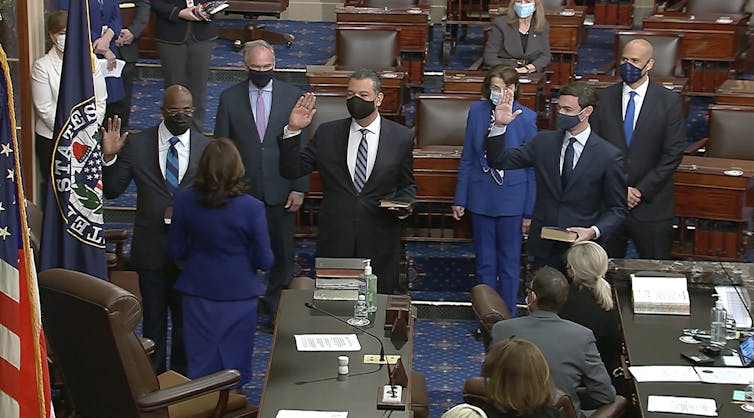

The first Jewish senator in Georgia history, Jon Ossoff, was sworn in on Jan. 20, on what his office described in a tweet as a “Hebrew scripture that belonged to historic Atlanta Rabbi Jacob Rothschild.”

It left many wondering what exactly the Hebrew scripture meant, and what the relevance was of using this particular copy.

The term “Hebrew scripture” usually refers to the 24 books that Christians denominate as the Old Testament. These biblical books, originally written in Hebrew, are ordered differently in Judaism and Christianity.

In Ossoff’s case, the volume selected was a well-thumbed copy of the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible, which Jews known as the Torah, edited with commentary by the American-educated former Chief Rabbi of Britain Joseph H. Hertz. That, for many years, was the edition of the Torah found in most American synagogues and temples.

As a scholar of American Jewish history, I recognize that in emphasizing the book’s tie to Rabbi Jacob M. Rothschild, Ossoff appeared to be making a statement about Black-Jewish relations – a central theme in his campaign and a signal of his ties to Congressman John R. Lewis, his mentor, as well as Rev. Raphael Warnock, his fellow incoming Georgia senator.

A Jewish translation of Scripture

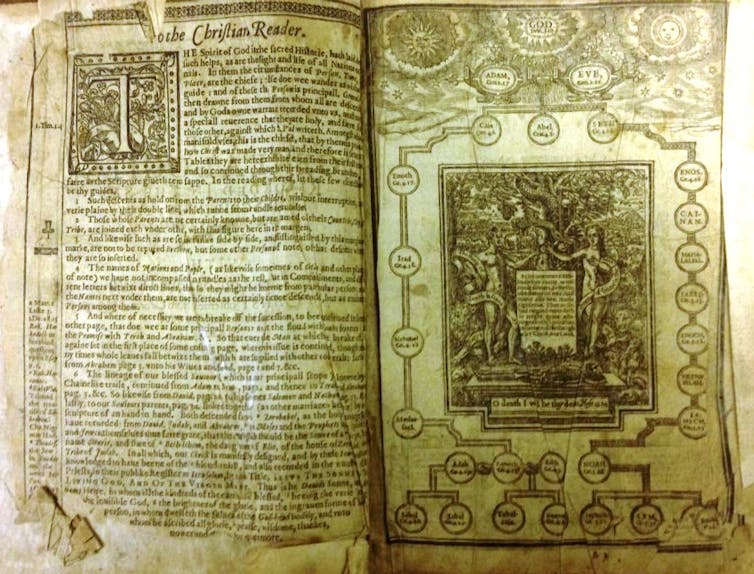

First, the selection of the Bible upon which Jon Ossoff was sworn deserves attention. This Hebrew-English text employs the 1917 translation produced by the Jewish Publication Society, then located in Philadelphia.

It is a distinctive Jewish translation of scripture. Though modeled on the majestic language and cadence of the famous King James Bible, authorized by the Church of England and first published in 1611, it nevertheless introduced many new translations from the original Hebrew based on updated scholarship and longstanding Jewish interpretive traditions.

“It was a Bible translation to which American Jews could point with pride as the creation of the Jewish consciousness on a par with similar products of the Catholic and Protestant churches,” historian Abraham Neuman observed in 1940. “To the Jews it presented a Bible which combined the spirit of Jewish tradition with the results of biblical scholarship, ancient, medieval and modern. To the non-Jews it opened the gateway of Jewish tradition in the interpretation of the Word of God,” he noted.

Thanks to the 1917 translation, American Jews no longer had to depend on other translations to understand “their Bible” – they now had a Bible translation of their own.

Ossoff was making a profoundly Jewish statement in selecting the volume on which he was sworn in. Earlier, President Biden made a similar Catholic statement by being sworn in on a Celtic Bible featuring the Catholic Douay-Rheims translation, published in the 17th century to uphold Catholic tradition in the face of the Protestant Reformation.

Atlanta’s rabbi

The book itself belonged to Rabbi Jacob M. Rothschild, who served from 1946 until his death in 1973 as the rabbi of Atlanta’s oldest and most prominent Reform congregation, Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, known as “The Temple.”

As an outspoken proponent of civil rights, he supported school desegregation; invited Black clergy like Benjamin E. Mays, president of Morehouse College, to speak to his congregants; and wrote that Jews bore a special responsibility “to erase inequality.”

To punish Rothschild and as a warning to others, white supremacist members of The Confederate Underground, a collective name for various right-wing extremist organizations in the 1950s, on Oct. 12, 1958, bombed The Temple, in a blast that was reportedly felt for miles around.

Until the mass shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue almost exactly 60 years later, on Oct. 27, 2018, the temple bombing was the most devastating attack in history on an American synagogue. Rothschild refused to be frightened off and remained at The Temple’s helm.

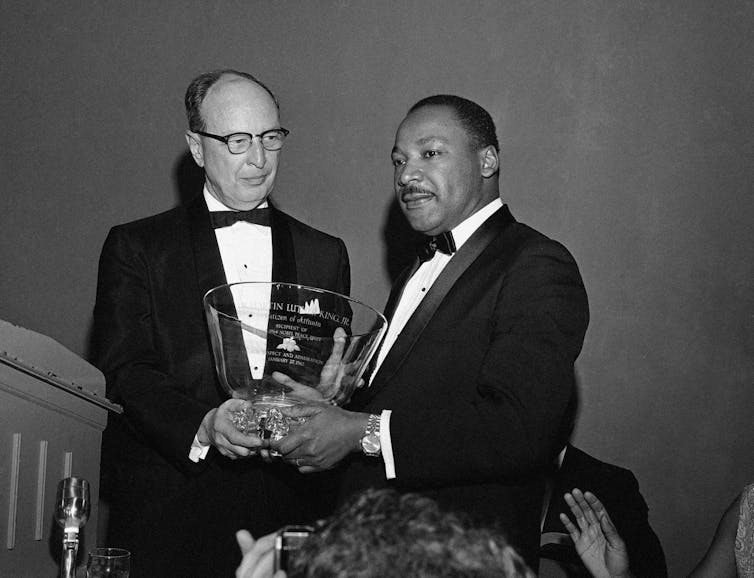

In the 1960s, Rabbi Rothschild met Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who had joined his father as co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church. The Rothschilds and the Kings became friends, and, in 1963, Rothschild introduced King when he spoke before a packed audience of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, known today as the Union for Reform Judaism, at its biennial gathering.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

Later, he played a central role in organizing a large Atlanta dinner honoring King for winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. When King was assassinated in 1968, Rabbi Rothschild delivered the eulogy at the city-wide service in Atlanta in his memory.

Rothschild’s message and Ossoff’s

Citing the same biblical passages heard at President Biden’s inauguration, Rothschild called for America to become “a land where a man does not lift up sword against his neighbor, but where each sits under his own vine and under his own fig tree and there is none to make him afraid.”

In deciding to be sworn in on the “Hebrew scripture” that belonged to Rabbi Rothschild, Senator Ossoff gestures back to this relationship that once brought Black and Jewish Americans together in a common quest.

In this gesture, he is delivering the same message as King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, did in 1984, when she wrote that the story of Rabbi Rothschild serves as “an inspiring story of commitment and brotherhood during an exciting, creative period of American history.”![]()

Jonathan D. Sarna, University Professor and Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History, Brandeis University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.