WandaVision’s Similarities to Recovery Journeys

Mary Rose Somarriba

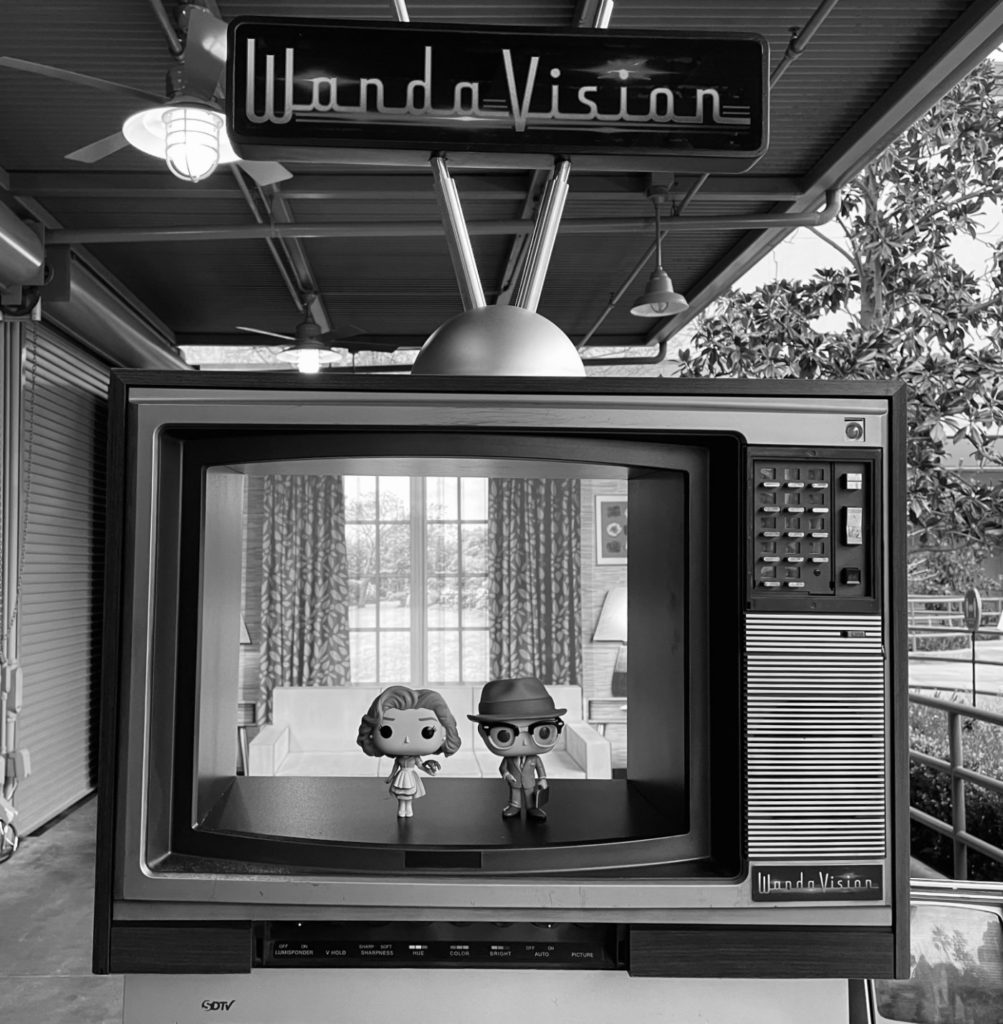

WandaVision, the Disney+ show that quickly became the most streamed show on any platform when its season began in January, is different from other comic superhero shows and movies. It takes viewers along a journey of recovery in an unexpectedly vivid way.

Superhero stories, often containing plots of good vs. evil, with endurance and virtue for the win, may never go out of style. While some think focusing on superheroes can distract from human struggles, I have always found superhero stories to be great analogies for the challenges of real life, even a life of faith. WandaVision was no different. In this show, through the lens of imperfect superheroes, viewers walk a humbling path through cripping hardships and wrongdoing toward redemption.

Those looking for action and comedy in their superhero storylines were jarred when the Marvel show started out in a way that was distinctly slow, opaque, and sad. It turns out the creators of WandaVision did this intentionally. While viewers everywhere were pulling out their hair wondering what they had just watched by the time the credits rolled, saying “Please Stand By,” somewhere the show creators were smiling, as this is just what they envisioned.

This is because WandaVision tells a story distinctly about an individual person’s recovery journey. Wanda Maximoff (Elizabeth Olsen), who was raised in a war-torn region, lost her parents at a young age, and was manipulated by a terrorist organization for some time before emancipating herself and joining the Avengers, has a lot of built-up trauma, it turns out. And unfortunately, even for superheroes, trauma doesn’t just go away by itself—it must be addressed, and that’s where recovery comes in. And recovery is a messy but essential road that, according to 12-step programs, requires surrendering to a higher power and taking one step at a time. For WandaVision, it starts with one befuddling episode at a time, as the protagonist tries to forge a path all by herself.

“This is essentially what we envisioned from the very beginning.” Jac Schaeffer, the show’s executive producer and head writer shared in an interview with Deadline. “This was always going to be a story about grief, and we took that seriously, and it’s a little bit reductive, but we used the stages of grief to map out the arc of the season, and we knew that we wanted to take it to a place of acceptance.”

Wanda’s “history in the comics is one of loss,” Schaeffer notes. “She’s been a more serious character and a character who at times seems locked into her own sadness and mourning…. in the comics and in the [Marvel Cinematic Universe] his woman has endured more loss than perhaps anyone, and that was the thing that we wanted to explore and work through with her.”

According to Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s groundbreaking work on grief, grieving persons often go through five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Kubler-Ross’s work continues to endure, and faith communities have merged Biblical references for each stage of grief. Grief expert David Kessler, who worked with Kubler-Ross and aspires to continue her work, since added a sixth stage, finding meaning.

If you or someone close to you has experienced trauma or immense grief, you may know how, if not properly addressed and healed, unresolved issues can manifest in one’s life in unexpected and unhealthy ways. Further, the path to recognizing the problem and recovering from it can include some wrong turns and winding roads before one makes it to the destination of acceptance.

This is well illustrated in Wanda’s story, as she grapples with the loss of her soul mate Vision. At first, her grief is expressed via “her desire to live in this fantasy world.”

“We start in denial with her and then we move into anger,” Schaeffer explains. And then in the penultimate episode, Wanda experiences a “full discovery of the stages of her life and really how this happened, that she has to face that in order to move forward, and that’s really…you know, it’s sort of the idea that she has to go to the arsenal in order to have the weapons in order to vanquish the bad guy in the end. Well, in this case, it’s grief. So, she needed to look everything in its face in order to be armed with what she needed to triumph and heal at the end of the story.”

Out of the depths

By the time I got the hang of what was happening in the series, I was impressed with the depth to which the show writers went in expressing the difficulty of facing mental health challenges that can extend from trauma and grief, including temptations toward denial and even controlling and manipulative tendencies to avoid facing the truth. For some, substance abuse, addictions, and other unhealthy habits can grow, as one attempts to cover up the festering issues they’re ignoring. When this happens, many people get hurt along the way. Twelve-step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous and their many offshoots were created for the very purpose of helping people overcome these challenges and face their trials head-on with humility and fellowship; meanwhile, support groups like Al-anon help loved ones recover from the pains of witnessing the dysfunction.

For Wanda, her unhealthy coping mechanism comes in the form of enslaving hundreds of people in her fantasy world, to avoid facing the difficult truths she avoided. As the series end neared, I watched with great anticipation, knowing something had to give—either she was going to fall flat on her face in her delusion, or wake up and make things right.

The series’ end is not perfect, as Arriving at Amen author Leah Libresco Sargeant notes in an article at Mere Orthodoxy. Just when the climax could explore what it means for Wanda to turn from her ways and make amends to those she’s hurt, a major deflection pops up in the plot. “Wanda begins to acknowledge her responsibility for the world she’d made,” Libresco Sargeantwrites. “But, just as she began to consider her own role as a villain, she was let off the hook by that most hackneyed of television devices: a final act twist.” A new villain, a witch named Agatha Harkness (Katherine Hahn), emerged to distract from Wanda’s wrongdoing. “By chaining Wanda up, Agatha was setting her free from the duty to put things right.”

The appearance of a new villain toward the end almost had me convinced that the show writers were showing again a pitfall many experience on the path to recovery—the temptation to blame someone else and continue avoiding the necessary work of recovery. Recovery work (connecting with a support group, seeing a trauma specialist therapist, and staying the course) may not be easy or fun, but it’s necessary for one to stop hurtful coping mechanisms and get one’s life back. So when a new villain showed up, I thought surely this was another one of Wanda’s imaginations, another delay on her odyssey toward healing.

“In our own lives, we succumb to the same temptation, retelling our stories with new, all-powerful villains,” Libresco Sargeant writes. “We cast ourselves as powerless in order to let ourselves off the hook for whatever we’ve left undone. It can be tempting to dream of martyrdom at the hands of an implacable enemy while neglecting our neighbor.”

As it turns out, however, the writers of WandaVision intended Agatha as a real villain, not just a deflection of Wanda’s doing, and the final episodes explode with the type of fight scenes one’s come to expect from Marvel movies. It is still a comic-book show at the end of the day, and the writers take some cartoonish liberties in wrapping up its plot. But, however imperfectly, Wanda does face her wrongdoing, undoes what harm she can, and accepts her loss in the process.

As Wanda’s fantasy world dissolves, Libresco Sargeant writes, “she’s left standing on a bare foundation—something real, at last, to build on.” While that may not be as pretty to look at as one’s delusions, it’s a lot more meaningful and reaps a lot more rewards. For Wanda, she’s traveled the five steps of grief and continues on toward meaning and redemption—her superhero saga mirroring aspects of the ever-universal human journey.