Why Shinto is attracting American followers

American Kit Cox, 35, works as an electrical engineer and enjoys biking and playing piano. But what some might consider surprising about Cox, who was raised as Methodist, is that she practices the Japanese religion known as Shinto.

While Cox’s interest in Shinto was originally sparked by her love for Japanese popular culture and media, Shinto practice is not just a phase or fad for her. For over 15 years, she has venerated Inari Ookami, a Shinto deity or “kami” connected to agriculture, industry, prosperity and success.

After several years of study, Cox received a great honor from Fushimi Inari Taisha, one of Japan’s most popular Shinto shrines. She was entrusted with a “wakemitama,” a physical portion of Inari Ookami’s spirit, which is now housed in a sacred box and enshrined in her home altar.

What’s more, Cox has emerged as a leader within a relatively small but growing community of Shinto practitioners scattered around the world. Her goal: to help Japan’s “indigenous” religion go global.

As an anthropologist of Japanese religion studying the spread of Shinto around the world, I met Cox where most non-Japanese people interested in Shinto do – online. Over several years of studying social media posts, participating in livestreams and conducting surveys and interviews, I’ve heard many people’s stories of what draws them to practice Shinto and how they navigate the difficulties of doing so outside of Japan.

What is Shinto?

Shinto has many faces. For some, it is a reservoir of local community traditions and a way of ritually marking milestones throughout the year and in one’s life. For others, it is an institution that attests to the Japanese emperor’s divine status as a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu or a life-affirming nature religion.

But at its core, Shinto is about the ritual veneration of kami.

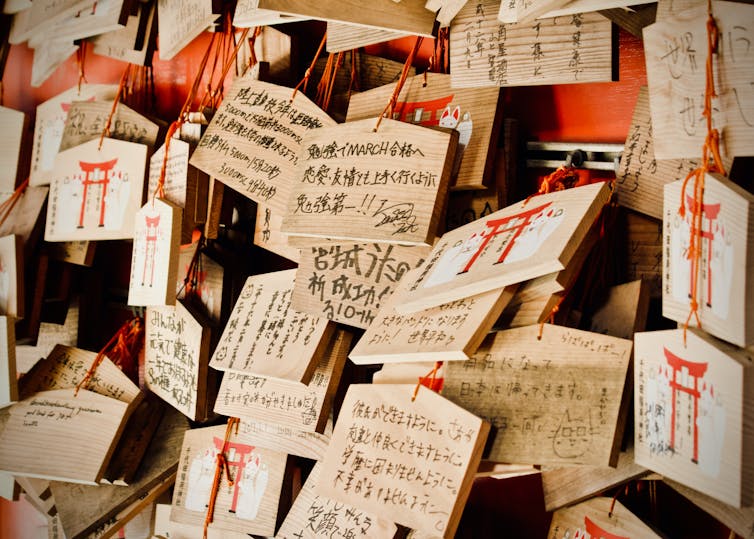

These myriad deities can take different forms. Many are associated with features of the natural world, like lightning and the sun, while others look after human concerns, from marital relationships to acing one’s college exams.

One of Shinto’s primary concerns is the management of spiritual impurities through ritual purification. According to Shinto thought, impurities accumulate simply as a product of living in this world, as well as through contact with sources of impurity, such as death or disease, and committing inappropriate acts. Because spiritual impurities offend the kami and are capable of threatening social order and people’s well-being, Shinto priests must purify them regularly through ritual.

Besides purification, Shinto also provides what contemporary Japanese religion experts Ian Reader and George Tanabe Jr. call “practical benefits.” These innumerable benefits include good health, prosperity and safety.

At Shinto shrines and in other sacred spaces, both priests and regular folks from all walks of life perform rituals to express gratitude for the deities’ protection and pray for their continued blessings.

Why do people choose Shinto?

While Shinto is often characterized as the “indigenous” religion of Japan, it is not limited by geography, nationality or ethnicity.

Non-Japanese people have received certification as Shinto priests, and Shinto shrines can be found around the world, including in the United States, Brazil, the Netherlands and the Republic of San Marino.

Global practitioners stress that, unlike many organized religions, Shinto has “no founder, doctrine, or sacred texts.” The majority identify as “spiritual but not religious,” a growing category of people who define spirituality as “personal, heart-felt, and authentic,” as opposed to the hierarchy and dogma of institutional religion.